Abstract

Measles, a highly contagious disease, can be effectively prevented through vaccination. The body’s cellular and antibody responses play crucial roles in combating this infection. However, in individuals with compromised immune systems, measles can manifest in a more severe form.

In this study, we highlight a case of measles wherein a robust antibody response developed weeks after the initial onset of infection in an individual with a healthy immune system. The patient, a 21-year-old male soldier, was admitted to the hospital exhibiting symptoms including high fever, coryza, rash, and headache, which had begun four days prior. Based on these symptoms, measles was suspected, and serological tests confirmed IgG positivity for measles, while IgM levels were initially just below the threshold.

Notably, a significant increase in IgG index values was observed one week later, followed by the detection of measles IgM two weeks post-onset. This rise in IgG levels played a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis. In cases where the IgM response is delayed or absent within the expected timeframe, monitoring for substantial elevations in IgG index values becomes pivotal. Additionally, direct diagnostic tests such as detecting measles RNA in upper respiratory tract samples and urine can provide valuable diagnostic insights.

Introduction

Measles (rubeola) is a contagious disease primarily observed in childhood and can be prevented through vaccination. However, due to factors such as vaccine refusal, lack of access to vaccination, and inadequate storage conditions, sporadic endemic outbreaks among adults can occur.

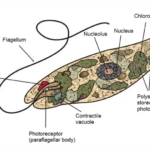

The measles virus belongs to the enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus genus Morbillivirus within the Paramyxoviridae family. Clinical manifestations of measles include high fever, maculopapular rash, conjunctivitis, cough, and nasal discharge. Complications are typically associated with the respiratory system and the central nervous system (such as pneumonia, blindness, and brain damage).

Both cellular and antibody responses are crucial in combating this infection. The measles virus has multiple receptors, with the primary receptor being the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM). Additionally, the virus can enter cells by binding to CD46 receptors on macrophages through hemagglutinin. Binding to its receptor can suppress the production of IL-12, necessary for cellular immunity, leading to anergy that can last for weeks. The disease can progress severely in cases of cellular immunodeficiency.

In this paper, we present a case of measles where an adequate antibody response occurred weeks after the onset of infection in an individual with a healthy immune system.

Case Report

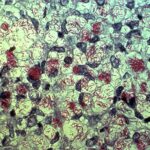

A 21-year-old male soldier presented to the hospital with a fever, runny nose, rash, and headache that had started four days prior. On examination, a maculopapular rash with blanching was observed on the body (Figure 1), along with conjunctival hyperemia and oral enanthema (Figure 2). His temperature was measured at 38.1°C. Laboratory tests revealed lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia. His childhood vaccinations were not definitively documented. Considering measles as the primary diagnosis, serological tests were conducted, revealing positive anti-measles IgG (439.8 IU/L) and negative anti-measles IgM (index value 0.7: close to the borderline negativity – borderline value: 0.8-1.1). Meanwhile, other soldiers in the same ward as the patient were screened and included in a prophylaxis program by the health department. Within 1-2 days of the patient’s presentation, four additional soldiers with similar symptoms were reported, and they tested positive for anti-measles IgM. The patient received vitamin A supplementation, anti-inflammatory treatment, and hydration therapy during his hospital stay. A repeat measles serology one week later showed weakly positive anti-measles IgM and positive IgG (4720.80 IU/L). His leukopenia and thrombocytopenia resolved during follow-up. The patient’s rash improved, oral intake returned to normal, and two weeks after admission, his measles IgM value became positive. He was discharged home upon clinical improvement. Written consent was obtained for the use of the patient’s medical information and photographs.

Measles IgM positivity is typically detected approximately 30 days after the onset of rash. Conversely, anti-measles IgG reaches its peak level around 14 days after rash onset and provides lifelong immunity. In this case, measles IgG was consistently positive, with a sudden elevation observed in IgG values during consecutive weekly tests. This finding served as a guiding factor in an atypical case regarding IgM serology. The measles virus can suppress T-lymphocytes, leading to anergic reactions, which may also inhibit the development of antibody responses (such as IgM response), as seen in this case. In instances where IgM response is not detectable, direct diagnostic tests, especially detecting measles RNA in upper respiratory tract samples and urine, can be beneficial.

A few days after the patient presented with typical measles symptoms, the appearance of infection symptoms in contacts and the detection of positive measles IgM antibodies in serum samples from these contacts aided in confirming our patient’s diagnosis. While ongoing low-level measles infection in the community is the most likely cause of measles infections in adult patients, other potential sources of measles should also be considered. Despite detailed history-taking, no information regarding possible contact with a suspected or confirmed measles case could be obtained for our patient. In outbreaks where the index case cannot be identified, a history of travel is often encountered among cases. Our patient had been serving in the same unit for approximately six months and denied any travel history outside the military premises. However, due to the inability to thoroughly question all individuals within the military community, the possibility of being in contact with an individual, either domestically or internationally, cannot be ruled out.

It was unclear whether our patient had received a measles vaccine in the past. In a study by Zhang et al., it was reported that 73.3% of individuals infected with measles had previously been vaccinated against measles.

Discussion

Serology (anti-measles IgM) is the most common laboratory method used in diagnosing measles virus infection. Detection of measles-specific IgM in serum or oral fluid confirms the diagnosis of acute infection. Additionally, a four-fold increase in specific IgG titers between serum samples taken two weeks apart can also aid in diagnosis. Anti-measles IgM can typically be detected around three days after the onset of rash; in such cases, it is recommended to confirm the diagnosis by taking another serum sample 3-5 days later. In a study by Karakeçili et al., measles IgM was found to be negative in 32% (9/28) of initial serum samples, but subsequent repeats yielded positive results. Another retrospective study examining 19 adult patients diagnosed with measles found IgM positivity in all patients, while IgG positivity was observed in only two patients. In another study focusing on sporadic cases, a similar trend was observed.

In conclusion, serology (anti-measles IgM) is the most widely used laboratory method in diagnosing measles virus infection. However, it should be noted that there can be atypical cases in terms of IgM serology. In cases where measles IgM response is not positive, direct diagnostic tests, especially detecting measles RNA in upper respiratory tract samples and urine, along with monitoring for an increase in IgG antibody levels, can be beneficial.