In the realm of diseases causing fatalities worldwide, infections leading to diarrhea rank second. These infections pose significant mortality and morbidity particularly among the elderly and children under 5 years old. Especially in developing regions like Asia and Africa, it is estimated that 4-6 million children succumb to diarrhea annually. The mortality rate due to diarrhea in children under 5 years old is recorded at 15.4% in Turkey, while globally it stands at 16.8%, as per the 2004 mortality data provided by the World Health Organization.

Diarrhea is defined as an increase in the frequency of bowel movements, accompanied by a decrease in absorption or an increase in secretion in the intestines, resulting in an excess of stool volume, an increase in daily stool frequency, and a change in stool consistency to soft and watery. Various factors such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites can cause diarrhea. In developing countries, bacteria and parasites predominantly contribute to diarrhea, whereas in both developed and developing nations, viruses are commonly implicated.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) has significantly increased in importance as a causative agent of diarrhea over the past 25 years. This escalation is attributed to the growing body of knowledge concerning the mechanisms through which different strains induce diarrhea. Among the bacterial agents causing diarrhea, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Vibrio, and the relatively harder-to-diagnose E. coli due to their presence in normal flora, hold notable positions.

MICROBIAL FLORA

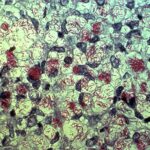

The gastrointestinal system harbors a vast array of normal flora elements in both quantity and diversity. Although gastric acidity in a normal host often prevents colonization to a significant extent, many bacteria manage to overcome this barrier and establish themselves in the lower gastrointestinal system, becoming permanent members of the flora. Typically, the upper small intestine contains few flora elements (10-10^3/ml of bacteria, primarily streptococci, lactobacilli, and yeast), whereas the distal ileum harbors predominant bacteria from the Enterobacteriaceae family and Bacteroides spp., ranging from 10^6-10^7/ml.

Infants usually become colonized with Staphylococci, Corynebacterium spp., and other gram-positive organisms (such as bifidobacteria, clostridia, lactobacilli, and streptococci) found in human epithelial flora shortly after birth. Over time, the composition of the intestinal flora changes. In adults, the normal flora of the large intestine is primarily colonized by anaerobic species, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Eubacterium.

Aerobic bacteria such as Escherichia coli and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, enterococci, and streptococci, are less abundant compared to anaerobes, with a ratio as low as 1000:1. The number of bacteria per gram of feces increases as it approaches the sigmoid colon within the intestinal lumen. In a healthy individual, approximately 80% of the dry stool weight, equivalent to around 10^11-10^12 CFU/g of bacteria, is comprised of microbial flora.

Escherichia coli as a Causative Agent of Diarrhea

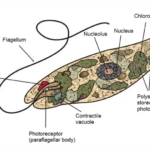

Escherichia, Shigella, and Salmonella are gram-negative rods belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae group, thriving well in MAC and causing diarrheal illnesses. Their motility is facilitated by peritrichous flagella. However, some strains of Shigella and certain origins of Escherichia and Salmonella are non-motile. They all ferment D-glucose, with Escherichia and Salmonella species typically producing gas. Phenotypically, Shigella bears resemblance to E. coli, and apart from Shigella boydii serotype 13, they can be considered the same species through DNA-DNA hybridization analysis. Within the Escherichia genus, there exist six species: Escherichia albertii, E. blattae, E. coli, E. fergusonii, E. hermannii, and E. vulneris, with E. coli embodying the typical characteristics of this genus.

Clinical Significance

Among the six Escherichia species, E. coli is commonly isolated from humans. It constitutes a permanent member of the intestinal flora in healthy individuals, yet certain strains can cause intestinal or extra-intestinal infections in both immunocompromised and healthy individuals alike. These infections vary from urinary tract infections, bacteremia, sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis, and diarrheas ranging from watery stools to dysentery-like symptoms, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS), and other infections. The dual nature of E. coli, as both a member of the normal flora and a frequent cause of diverse infections, has intrigued researchers, leading to its selection as a model organism for scientific investigations. As a result of these studies, the complete genome of the bacterium has been sequenced.

Pathogenesis

The development of infection in the gastrointestinal system follows a pathogenesis similar to that of urinary tract infections. Whether an intestinal pathogen leads to diarrhea is determined by the unique characteristics of the host and the invading microorganism.

In the gastrointestinal tract, the process unfolds with the interplay between the host’s defenses and the virulence factors of the invading microorganism. The ability of the pathogen to adhere to and colonize the intestinal epithelium, penetrate the mucosal barrier, and produce toxins plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal infections.

Furthermore, the host’s immune response, including both innate and adaptive mechanisms, influences the severity and duration of the infection. Factors such as the host’s age, nutritional status, and underlying medical conditions also contribute to the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal infections.

Understanding the intricate interplay between host and pathogen is essential for developing effective preventive measures and therapeutic strategies against gastrointestinal infections. Research in this field continues to uncover new insights into the pathogenesis of these infections, paving the way for improved diagnostics and treatments in the future.

Putative Escherichia coli Implicated in Diarrhea

Several putative pathological types have been identified. However, in volunteer studies or outbreak investigations, none of these types have been conclusively shown to be virulent. Escherichia coli (DAEC) demonstrating characteristic diffuse adherence to Hep-2 cells is implicated as a cause of diarrhea in some epidemiological studies, while in others, no association has been found; it has been established that the prototype strain of DAEC does not induce diarrhea in adult volunteers. Some studies suggest that DAEC infection may be associated with watery diarrhea in children aged 1-5 years but not in newborns. DAEC can be observed in industrialized countries.

Research into putative Escherichia coli strains continues, aiming to clarify their role in diarrheal diseases and their pathogenic mechanisms. Understanding the complexities of these strains’ interactions with the host and their ability to cause disease is crucial for developing targeted interventions to prevent and treat diarrheal illnesses effectively. Ongoing epidemiological studies and advancements in molecular biology techniques hold promise for unraveling the mysteries surrounding these putative pathogens.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Escherichia coli is a bacterium that can grow even on simple culture media and is easily isolated from cultures. However, many characteristics of E. coli strains that are normally commensal in the intestine and non-pathogenic are shared with pathogenic strains. Therefore, distinguishing virulent types from E. coli strains found in fecal flora makes diagnosing intestinal infections challenging. Numerous diagnostic methods have been described to detect the antigens, toxins, and virulence genes of diarrheagenic E. coli. While these methods generally successfully identify pathogenic E. coli types, some are not yet suitable for routine use.

Efforts continue to refine laboratory diagnostic techniques for E. coli infections, aiming to enhance accuracy and efficiency in identifying pathogenic strains. Advancements in molecular biology and diagnostic technology offer promising avenues for the development of improved diagnostic assays, enabling faster and more reliable detection of diarrheagenic E. coli strains in clinical and public health settings.