Overview: Pathology and Mechanism

Salmonella was initially confirmed by British and German bacteriologists in the 1880s, including Robert Koch, and named in honor of Daniel Elmer Salmon, an American veterinary pathologist working with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) research team.

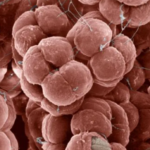

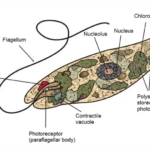

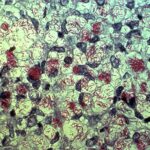

Salmonella is a facultative anaerobic, motile, non-spore-forming, rod-shaped, gram-negative enteric bacterium in the Enterobacteriaceae family. Most strains of Salmonella are H2S positive (producing hydrogen sulfide, which leads to the characteristic odor of stool). Their sizes range from 2 to 5 μm (micrometers). Within this genus, there are two species: Salmonella enterica and Salmonella bongori. Salmonella enterica includes six subspecies and 2,600 serotypes (variants based on surface antigens) within its spectrum. This species is present in all warm-blooded animals and their environments worldwide, with a particular prevalence in reptilian floras.

Source: Microscope World

Symptomps And Signs

Known for causing infections within the gastrointestinal (digestive) system, leading to diarrhea or dysentery, Salmonella is associated with a condition called salmonellosis. This disease is zoonotic, meaning it can spread between humans and animals through direct or indirect means. Typically, a unit capable of forming 10 colonies per gram of feces, or 10 CFU/g, is sufficient for an infection to occur.

Salmonella is a natural pathogen found in the intestines of humans and animals, with the highest prevalence observed in poultry and eggs. Pork is also considered a high-risk group because this bacterium has been isolated even from live pigs’ mouths. Additionally, water contaminated with feces and any food processed with such water poses a risk. Instances of this illness have been most frequently identified in places where mass meals are produced and consumed, such as cafeterias, dormitory-hospital canteens, and restaurants. Some virulence properties are outlined below:

It exhibits resistance to extreme environmental conditions. For instance, while some strains can thrive at temperatures as high as 54°C, others display psychrotrophic characteristics and can survive in foods stored at 2-4°C. It’s worth noting that the range of 2-4°C directly refers to refrigerator temperature for food engineers and microbiologists! It can survive for years under frozen storage conditions. For example, it has been isolated from frozen meat stored at -20°C for up to 1500 days. It can survive in a 8% salt concentration and has even been isolated from seawater, which has a much higher salt concentration. Due to its nature, it is resistant to bile salts and can therefore pass into the gallbladder. This feature will be further discussed in later stages, as the famous case of Mary is associated with this trait. It possesses a Chamomile-like Enterotoxin, with its B subunit adhering to the intestinal mucosa. Upon entry into the mucosa with antisin, it converts ATP to ADP, and ADP to CAMP (Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate), leading to an increase in CAMP causing opening of the channels in the cell, resulting in the outflow of minerals and water from these channels. Thus, diarrhea occurs. It contains a cytotoxin that is heat resistant and can be found in heat-treated foods. It possesses O antigen and causes septicemia. It raises the fever up to 41°C and reduces the phagocytosis activity of our defense cells.

Disease-Associated Genes, Causal Factors, and Risk Factors

At the outset, we mentioned the presence of flagella and the motility of this pathogen. Through these flagella, it adheres to the M cells in the intestines. After entering the intestinal cells with its enterotoxin’s antisin, it reaches the circulatory system it has an affinity for. Through the bloodstream, it first reaches the liver. By this stage, disease symptoms have likely already begun, and antibiotic treatment is often administered. If it fails to adhere to the liver due to treatment, it moves to the spleen. At this stage, the patient should be admitted to intensive care. If it also fails to adhere to the spleen, it moves to the gallbladder. Even if the patient recovers, from this stage onwards, they are likely carriers, much like Mary Mallon, with a 90% chance. Therefore, this patient will shed Salmonella every time they defecate. Mary Mallon was born in 1869 in Ireland and, although uncertain, migrated to America in 1883 or 1884 to work in a restaurant. Mary was a carrier and the interesting part is that she showed no symptoms of the disease. Investigations revealed that she was responsible for infecting approximately 3000 New Yorkers in 1907. Sanitary Engineer George Sober, who followed Mary, reported that Mary had developed resistance to Salmonella Typhi and isolated the bacterium in her blood and feces. The biggest handicap was the lack of antibiotic treatment until 1948. Mary, identified as a carrier, was quarantined in a hospital and discharged after a 2-year medical treatment, with a condition banning her from working in any food establishment. However, she did not comply with this ban and started working in another restaurant under a false name. Within 3 months of starting work, she infected at least 25 people, two of whom died. When it was determined that Mary was responsible for the outbreaks, she remained hospitalized until her death in 1938.

Diagnostic Methods

Diagnosis can be established by detecting DNA using the PCR method. For the identification of Salmonella species, various agar media such as EMB agar, SS agar, XLD agar, HE agar, and DCA agar are used for cultivation, followed by identification based on biochemical characteristics such as lactose utilization and H2S production. Serotyping is carried out according to the Kaufmann-White scheme. After detecting positivity with Salmonella poly O antiserum, agglutination continues with monovalent antisera. For molecular typing, the gold standard method is pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Serological diagnosis is conducted using the Gruber-Widal test.

Treatments or Management Methods

Antibiotic treatment is not routine for Salmonella gastroenteritis, as the disease typically resolves on its own. However, definitive treatment for Salmonella involves antimicrobial (antibiotic) drugs. Given that they are enteric bacteria, the first choice among these drugs should be from the fluoroquinolone group, specifically ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin. In pregnant women and children, third-generation cephalosporins like ceftriaxone can be used. Strains resistant to famous beta-lactam antibiotics like ampicillin and amoxicillin derivatives have developed resistance to ESBL (Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase). For ESBL (+) strains, ertapenem from carbapenems can be used. Although rarely used, chloramphenicol from older antibiotics may be considered. Azithromycin can be administered in cases of multi-drug-resistant enteric fever. Antibiotic therapy should be considered in immunosuppressed individuals, patients over 50 with atherosclerosis, organ transplant recipients, and those with significant joint disease. In these cases, drugs other than azithromycin and chloramphenicol mentioned above can be used in treatment.

Prognosis

Certain subspecies like Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi can cause typhoid fever by crossing from the lymphatic circulation of the intestinal system into the bloodstream, resulting in symptoms such as fever, vomiting, organ damage, and septic shock. Typhoid fever, typically transmitted through human feces and feces-contaminated food, has an incubation period (the time from infection to the onset of symptoms) of 8-10 days in adults and 1-2 days in children. The illness lasts approximately 20-30 days, with a mortality rate of around 10% in cases. However, it has not been observed in Turkey for several years now. There is also a paratyphoid serotype of the same subspecies, which tends to be milder than typhoid fever and has a shorter incubation period. However, it can lead to chronic diseases such as Reiter’s syndrome and ankylosing spondylitis. Salmonella Paratyphi and Salmonella Typhi are clinical names rather than taxonomic classifications. Salmonella eastborne is the most pathogenic strain, with an infective dose of 1/gram.

Frequency and Distribution (Epidemiology)

According to the statement from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Salmonella accounts for one out of every three foodborne outbreaks in the European Union in 2018, making it the second most common microorganism responsible for gastrointestinal infections. Each year, 91,000 cases of Salmonella-related illnesses are reported in the European Union.

Preventive Measures

Salmonella most commonly contaminates pasteurized food through post-contamination. Therefore, raw products and equipment in contact with these products should never come into contact with heat-treated products and equipment.

Personal hygiene and personnel hygiene are among the most important methods of protection against most foodborne infections.

After handling raw eggs and poultry, hands should be washed thoroughly with soap and water without touching anything else. This is because Salmonella naturally occurs on the skin, carcass, and feces of raw poultry. Similarly, it naturally contaminates the surface of eggs when chickens lay eggs.

They are not eliminated by freezing. They are destroyed in food brought to a central temperature of 65°C (through heat treatment) within 30 seconds. Therefore, cooked products are ideal for preservation. Although many of us enjoy them, we should avoid raw eggs.

Protective medicine should be mandatory, especially in the poultry industry, and slaughterhouses should be designed or improved to comply with HACCP standards.

The D-value (Decimal Reduction Time: the time required for a 1-logarithmic (%90) reduction in bacteria) ranges from 0.2 to 6.5 minutes at a temperature.

Etymology

It is named after Daniel Elmer Salmon, an American veterinary pathologist.