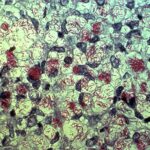

Throughout evolution, humans and all other animals have coevolved in close relationship with microbial communities consisting of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms. These collections of microorganisms, referred to as the microbiota, reside in almost every body surface exposed to the environment, with the gastrointestinal tract hosting the highest density and absolute abundance of microorganisms, known as the gut microbiota. Research indicates that the gut microbiota, far from being passive passengers in our bodies, plays a vital role in our immune system, metabolism, and even the development of various organs.

Why is the Gut Called the “Second Brain”?

The gut boasts a wide range of different signaling molecules, isolated nerves, and types of connections. Another organ with such diverse features is our brain. The intricate network of nerves in the gut is why it’s dubbed the “intestinal brain”; it’s a structure as vast and complex as the brain itself. Its technical name is the enteric nervous system.

Signals linked to the gut can reach various regions of the brain, although they can’t reach all areas. For instance, they can’t reach the area responsible for our vision, located at the back of the brain. If they did, we’d imprint gut activities as images and effects in our brain. The places these signals can reach include the insula, limbic system, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior cingulate cortex.

Furthermore, the gut microbiota can influence intestinal barrier integrity or portal circulation, controlling the passage of signaling molecules from the gut lumen to immune cells and the terminal ends of enteric nervous system neurons in the lamina propria. Disruption of intestinal barrier integrity can occur in some neuropsychiatric conditions like anxiety, autism spectrum disorder, and depression. Stress within the nervous system can also alter the gut environment and microbiota composition.

The Relationship Between Gut Infection and Depression

Initially, the connection between anxiety and gut microbiota was explored in the context of infection. Recently, a large longitudinal epidemiological study examined the relationship between gut infection and subsequent onset of anxiety disorder using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a public health-related survey set. The findings from the study indicate an increased likelihood of developing anxiety disorder in individuals previously exposed to gut infection, suggesting that the gut microbiota may serve as a potential “trigger” for subsequent anxiety disorder. Increasing evidence suggests that the gut microbiota could play a significant role in the pathophysiology of depression, although the specific molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

Depressive Mice and Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB-1

The forced swim test stands out as a highly impactful experiment concerning motivation and depression. In this experiment, a mouse is placed in a small pool where it cannot touch the bottom, thus initiating struggling motions to reach the safety of the platform. Mice exhibiting depressive traits tend to swim for shorter durations, displaying intermittent and reluctant efforts. Instead of being driven by motivating and activating impulses, their brains are dominated by inhibitory signals, with stress taking the forefront. Under normal circumstances, these mice can be subjected to antidepressant trials. A prolonged swimming duration after administering antidepressants serves as a significant indicator of the drug’s efficacy on the mice.

An Irish scientist, John Cryan, and his team took the forced swim test a step further. They fed some mice with bacteria responsible for gut cleanliness: Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB-1. As a result, these mice, with their rejuvenated gut flora, indeed exhibited more hopeful behavior, swimming for longer periods. A notable decrease in stress hormones in their bloodstreams was observed. Moreover, they outperformed others in memory and learning tests. However, the scientist’s decision to sever the vagus nerve in the mice setback their progress in this aspect, bringing them back to the same stage as the others.

The Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve stands out as the most crucial and fastest nerve in establishing communication between the intestine and the brain. It travels through the diaphragm, passes between the lungs and the heart to reach the esophagus, and then ascends upward through the throat to connect to the brain. An experiment conducted on humans revealed that stimulating this nerve at specific frequencies could make subjects feel more relaxed or become more apprehensive. In Europe, since 2010, a therapy method for depression involves stimulating the vagus nerve to a degree that leads to the patient’s recovery.

Bubble Experiment and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Communication between the intestine and the brain can be quite taxing for individuals with an irritable bowel. This phenomenon is evident even when brain tomography is performed. In one experiment, participants had a small air bubble inserted into their intestines, while the brain’s activity was monitored. Remarkably normal brain activity was observed in participants without complaints, with no emotional upheavals noted. However, in participants with irritated intestines, the presence of the bubble led to activation of other brain regions, which typically focus on discomfort under normal circumstances. Consequently, despite not having done anything wrong, participants felt unwell. This phenomenon is characteristic of “irritable bowel syndrome,” where individuals experience abdominal discomfort or rumbling. These sensations can eventually lead to diarrhea or constipation. Fear and depression often accompany individuals experiencing this syndrome.

The “bubble experiment” and similar studies clearly indicate that fatigue and negative emotions can arise in connection with this syndrome when the intestinal threshold is exceeded or when the brain insists on obtaining information.

Treatment of Depressive Behavior in Living Organisms

A group of researchers from China has demonstrated in laboratory settings that Lactobacillus reuteri possesses inhibitory properties on pain sensors found in the gut. Recently, Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium infantis have also begun to be used for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.

Hypnotherapy is another highly effective method for individuals complaining of irritable bowel syndrome. Typically, the job of hypnotherapists is to delve into the thoughts of the individual or stimulate their imagination. This helps alleviate pain signals and redirect focus to other points of interest. Just as exercises on muscles can lead to nerve development, these exercises can lead to nerve development as well. Many patients have significantly reduced their medication intake as a result of this therapy; some have even stopped using medication altogether.

Faced with a series of stresses, mice exhibited depressive behaviors and microbial dysbiosis, which were reversed with probiotic application, intestinal bacterial supplementation, or antibiotic treatment. The depressive-like behaviors were reversed with oral administration of albiflorin and Lactobacillus, and it was found that the altered gut microbiota was associated with depressive-like behaviors and varying levels of neurotransmitters. In particular, treatment with L. helveticus NS8 improved depressive-like behavior induced by chronic restraint stress and reduced cognitive dysfunction, with effects superior to those of the antidepressant citalopram.

Impact of Antidepressants on the Gut

Antidepressants like Prozac, which have become household names, convey significant information related to the “happiness hormone” serotonin. One in four individuals taking these antidepressants may experience side effects such as nausea, diarrhea, and constipation with prolonged use. This is because the gut contains receptors similar to those in our brain, so antidepressants affect both. American researcher Dr. Michael Gershon took his thoughts a step further and asked himself the following question:

Could antidepressants that only affect the gut and have no effect on the brain lead to positive or negative outcomes in some individuals?

This is not an entirely unrelated thought. Ninety-five percent of the serotonin produced in our body is synthesized by intestinal cells. Here, it not only moderates the effects of nerves on muscle movements but also assumes the role of the most important signaling molecule. Therefore, altering the effects in this area could lead to the transmission of vastly different signals to the brain. Interestingly, this could lead to an unexpectedly depressive mood in an otherwise thriving individual.

The Vital Role of Gut Microbiota in Depression

Currently, there are relatively few research teams focusing on the “brain-gut connection,” but those that do exist are quite proficient. The insights they gather are not only significant for those experiencing gut-related issues but are of great importance to all individuals. All studies conducted so far have clearly shown that externally induced dysbiosis in gut microbiota leads to disturbances in social behaviors, increases susceptibility to anxiety or depression, raises inflammation, and causes faulty nerve functions. All these findings from animal studies provide strong evidence for the vital role of gut microbiota in depression.

Anyone experiencing fear and depression should consider that a troubled gut could be a contributing factor. Sometimes, these emotions arise from excessive intensity or inadvertently consuming a food that doesn’t agree with us. Blaming solely our brain or past experiences would be incorrect, as we are more than just those factors.